In a previous post about the topic of constraint, I talked all about how using props as a form of feedback, or constraint can make for some pretty interesting movement explorations.

Using constraints has helped me be more creative and open in how I practice and teach physical postures in a variety of modalities.

But there’s something even deeper going on when we look at what constraints do “off the mat,” as they say.

Let’s go back to the block-head exercise, where I used the isometric connection between my head and the block to experience clearer neck alignment. Besides the analgesic (pain-relieving) effects of isometrics, this kind of constraint is a great way to experience a concept in anatomy that I love: the muscular slings. These groups of muscles, like rivers, flow in wrapping patterns around our whole body connecting our limbs and spine so that forces can be shared and amplified between them.

The block stimulates activation of these muscular continuities leading to a feeling of integration that clarifies our whole body’s inner portrait—helping us practice proprioception.

Now, this might sound like more movement-centric creativity, but stay with me. This cycle of feedback plays out in a complex way at the level of our nervous system is complex, and one (helpful) term that’s used to describe what’s happening is called body mapping.

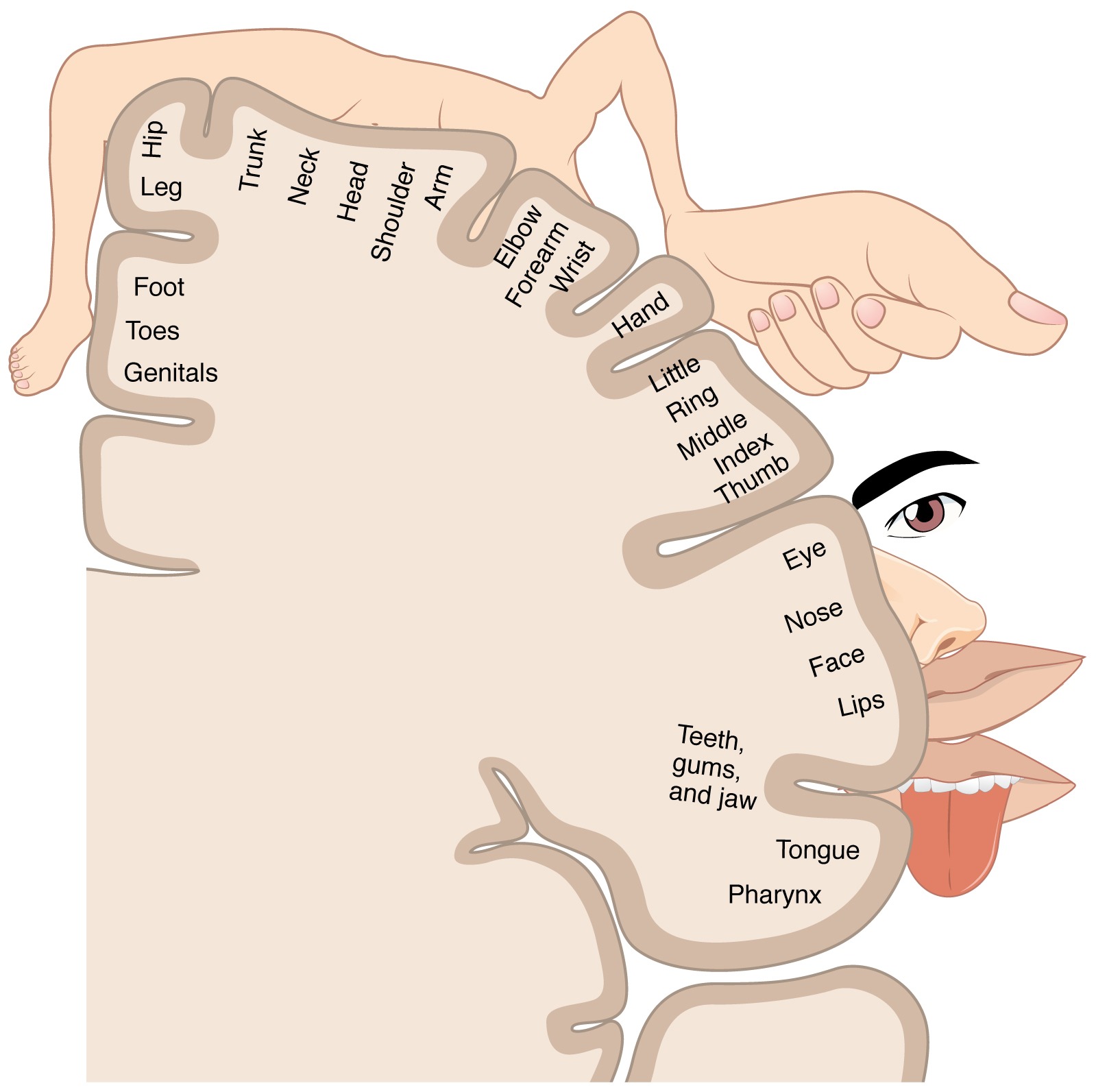

Our body is mapped onto our brain, and this map relate very closely to proprioception, or the complex mechanism by which we know where we are in space and how our body is moving.

The block, in a way, helps us to clarify our body map, which, for various reasons might be unclear, sometimes referred to as “smudged” (yes, that’s the technical term). If our body map is smudged, it’s almost as if you spilled coffee on your old-fashioned road map (you know the ones made of paper you have to look at carefully and decipher?), making it extra difficult to read. It’d be hard to make sense of that stained map. A similar thing happens in our bodies when the map of our body in our brain becomes smudged.

When your brain’s body map becomes smudged, for whatever reason—maybe you have some pain or you don’t move a lot in a particular way—you’ll have a hard time organizing body parts and joints involved in specific movements through space. You might feel lost, even if you’ve been to that place/shape/sequence in your body before.

This pandemic is a constraint of global proportions, affecting every person on the planet differently.

I’ll speak for myself only when I say that, if I think of the pandemic as a constraint, I see how it has indeed created limitations on what I would normally do and how I would normally spend my time. However, it’s also caused me to leverage my skillset and create value in new ways. It’s the reason I pivoted to teaching online, which eventually turned into creating my Virtual Studio.

I’ve experienced a similar lost-ness a few years back in my teaching. For a while, I felt trapped in dogma when I taught yoga, repeating the same old sequences and cues. I was also in physical pain from an excess of repetitive movement and a lack of diverse loading.

So, I started exploring other movement modalities. Slowly over time, this cross-pollinated and planted new seeds of ideas that inspired whole classes, and eventually transformed my teaching organically. I used an initial constraint to free up my teacher-brain to problem solve the reasons and solutions for my boredom and physical pain.

It also taught me that I value ideas over dogma. Today, my practice is continuously noting the difference between what I think and what I’m told, where these diverge, and where they overlap. In doing so, I make critical-thinking the bigger practice and what I’m actually presenting when I teach.

What I find so philosophically compelling, then, about the concept of constraint, is how yogic it is.

The term (and practice) makes space for opposites. It encourages us to set aside our lens of either/or and look instead through the lens of both/and. It makes space for a kind of mobility—a kind of freedom—that happens when we forget the map and look, instead, at the wide open landscape before us. Constraints can impel us to move in a specific direction, even when we have many options. This can feel like freedom when we feel pulled in too many directions at once.

Thinking about constraints in this way really explodes its meaning beyond props, or even movement. As the pandemic continues to impose constraints on my life during these months, I remain excited by what freedoms these limitations might further reveal.

Leave a Reply